What’s your relationship with anger? With your own anger and with the anger of others?

Do you often feel angry or not? Do you often express anger or not?

In general, are you comfortable with others expressing anger, or do you tend to react with fear or resentment or anger?

How does this change, depending on who is angry? How does this change, depending on the circumstances?

Then look at our society as a whole: are there differences in how people’s anger is treated, depending on who they are? Whose anger in general is respected and listened to? Whose anger is condemned and feared? Who is safe to express their anger? Who is not safe to express their anger?

And for all of this, I invite us to reflect on why?

What life experiences do you bring to your relationship with anger? How are there factors in the mix like gender and race and class and culture? What moral or religious lessons about anger have you taken to heart?

I ask all this because, well, anger is a big force within our human experience; anger does seem to be a big force in our public lives in these fraught times; and our Christian tradition has wise teachings about anger that could be helpful to how we seek to act with faith and integrity.

These teachings are more than just, “All anger is always bad.”

But wait, didn’t we just hear Jesus say “Don’t be angry”!?

And haven’t some of us been told this when we were angry, regardless of whether we were angry for good reason or for bad?

In Jesus’ teaching he quickly gets specific that he’s talking about how anger can drive us to use words to attack each other, insult each other. He’s talking about actions and the motivation for actions, not just about the feelings themselves.

The Apostle Paul gives us very helpful clarification: “Be angry, yet do not sin. Do not let the sun go down on your anger.”

This isn’t about somehow preventing ourselves from ever feeling angry. That’s an impossible standard. Rather, this is about being wise about what we do with anger when it does inevitably arise in us. Being wise means seeing that anger is the kind of emotion that if we just let it take over, it’ll lead to harm and suffering.

There can be a right relationship with anger, a wise relationship, a just relationship.

We have the famous story of Jesus going to the holy temple seeing the people getting rich off his people’s piety, and driving them out. He flipped over their tables with money scattering, sending them running. This is a dramatic act of justice. And it’s not hard to imagine Jesus doing this while feeling some righteous anger about this exploitation of people’s faith. It’s not hard to imagine Jesus feeling and doing the same in our day in with all the ways that religion is leveraged for wealth and power.

Then there’s the story of a man coming to Jesus in need of healing. It was the Sabbath and you’re not supposed to work on the Sabbath. Jesus challenged the people around him to tell him if it’s okay to work on the Sabbath for the sake of healing. But the people around him were a bunch of heart-hearted biblical literalists who said that any effort for any reason on the Sabbath was work and therefore forbidden.

Then, the gospel writer tells us, “Jesus looked at them with anger”

Jesus felt anger. But did he just stay angry and do whatever anger told him to do? No. The gospel writer tells us that the very next moment Jesus “was grieved at their hardness of heart.” He looked at them with anger and was grieved at their hardness of heart.

Beneath his initial anger was grief.

Grief, sadness: this is a great signal to us of whether our anger is legitimate, or if it’s just our own selfish blustering. A lot of anger, as you know, is just a whole lot of show, it’s an alpha ape throwing sand in the air. But if there’s grief along with the anger, it’s important to feel that deeper feeling and let that directs us to the legitimate harm that’s giving rise to our anger.

Jesus connects that harm to hardness of heart. His response is to open his heart. His anger does not lead him to meet hardness of heart with hardness of heart, but rather with openness of heart along with a bold, strong, clear act of love. He heals the man, in defiance of the uncompromisingly literalistic interpretation of scripture.

He felt angry, but he let that anger motivate him to do the right thing in the right way.

It’s not hard to imagine Jesus feeling and doing the same in this day in age with all the ways religion is used to make people less compassionate and more biased and judgmental.

One quick note: Jews for countless years now have rejected the Pharisee’s hard-hearted literalistic interpretation of Sabbath keeping. After Jesus there has been a long line of rabbis who have been very clear that, yes, for the love of God, if it’s the sabbath and you come upon someone in need of healing, you are obligated to heal them, and it’s a sin not too.

I hope these are helpful examples of a wise relation with anger, and why it’s important that we acknowledge when we are feeling angry rather than deny or suppress it. Sometimes we are angry for petty reasons, maybe a lot of the time. But sometimes anger can be an important signal to us that something is wrong that needs to be stopped or changed. Anger gives us a good dose of energy to do something about it. But what anger does not do is give us good advice about what we should do. So, we need to learn to redirect anger into productive and upbuilding and compassionate actions. Prayer, the practice of pausing and letting God into the mix, is a great tool for us here.

Biblical wisdom is very clear about the grave dangers of letting our anger do what it wants to do. This is also very important to be clear about in our day in age when anger is so dominate our public life.

In talking about this danger of anger, Jesus uses the stark language of Gehenna. Sometimes Gehenna is translated as hell, but what it literally meant was a burning trash heap outside town, where the bodies of executed criminals were dumped, and people used to offer child sacrifices. Jesus mentions Gehenna to mean a wretched spiritual state of suffering and misery. He uses it only a few times in the gospels, not even close to as often as those wrathful preachers who delight in condemning people to hell would have you believe. Jesus only talks about Gehenna to convey the spiritual consequences for those who harm and neglect the poor and the powerless, as well here in the context of vicious behavior due to anger. I truly believe this is a way of talking about a state of soul sickness that afflicts humanity in this life and perhaps into the next, that is a natural consequence of the violent denial of sanctity of others and ourselves, which can be relieved when we say Yes to the free gift of God’s grace.

If we do what anger tells us to do, this can indeed pitch us into an outer darkness where there is weeping and gnashing of teeth.

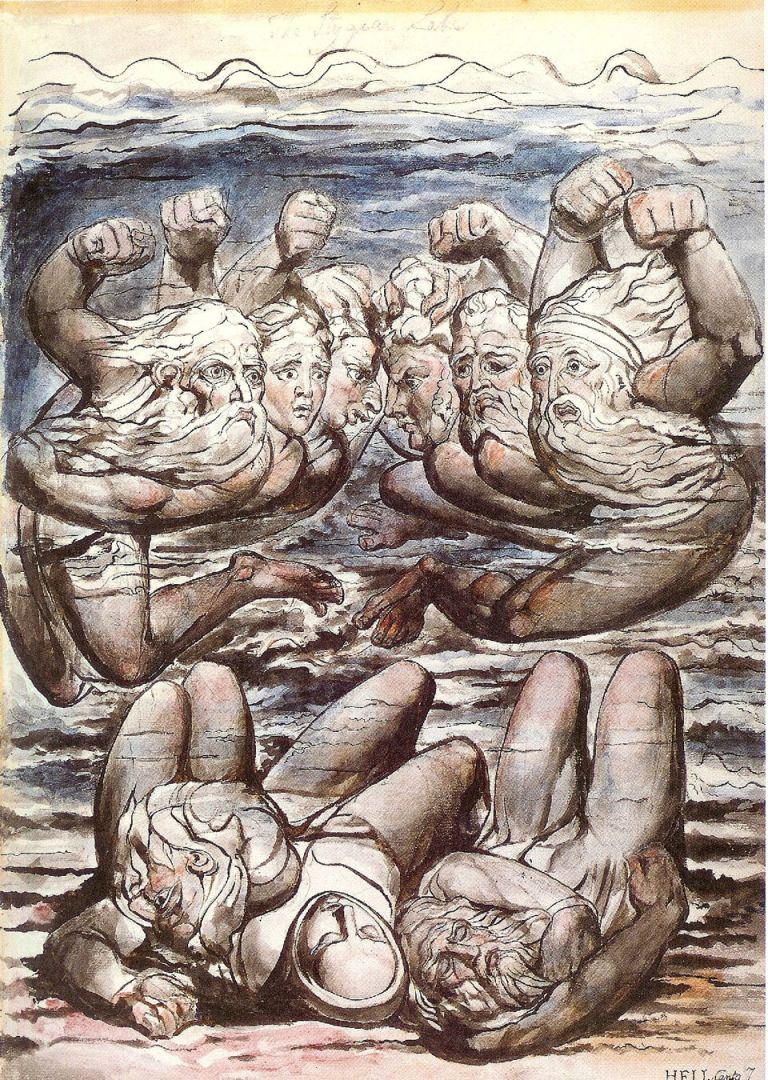

We’ve all heard of Dante’s Inferno, right? Famous work of epic poetry, a work of genius, full of psychological and spiritual wisdom. A mythological tale of the poet’s journey into the realms of hell, and up through purgatory and into paradise.

In Dante’s inferno, there’s a circle of hell that is the circle of anger. He describes it as being a quagmire – it’s a sticky, mucky bog of toxic sludge.

The souls that are stuck in this quagmire of anger are two types:

Those caught up in wrath and

Those caught in sullenness.

First, those who are wrathful. In Dante’s hell, they writhe around in the muck bludgeoning each other … for eternity, they beat and get battered in this never-ending battle of blame and bruised ego.

Maybe it’s thrilling for a bit, lashing out in anger, but a whole lifetime of it is either totally deadening or totally nauseating. War is hell. And whether the wars we’re caught up in are little or large, they have a way of trapping us in endless, repeating cycles of brutal strife. It’s a spiritual sickness.

This is the aspect of anger that Jesus warns against in our reading from Matthew, from the Sermon on the Mount. He’s pointing out the connection between acts of violence and the state of anger that leads to them. Anger often has this desire in it to get back at someone. If someone’s hurt me, or threatens to hurt me, or I think they’ve hurt me, or if they hurt someone or something I care about, I get angry and want to hurt them back.

So Jesus is saying, “Watch out for that anger, because it could pitch you into Gehenna.” when we answer violence with violence and meet hate with hate, we just get pulled down and get stuck in toxic sludge, and we need a Higher Power to get us unstuck.

So that’s the quagmire of wrath in Dante’s hell of anger. But wrath is only half of it. The other bunch of souls Dante calls “the Sullen.”

Dante depicts these souls wallowing at the bottom of the swamp. They’re depressed, defeated, drained out, sunken… This is a state of the soul that has repressed anger. This too is a type of hell.

So, we need to be able to do something with our anger. Something healthy and just and true. And when there is great harm and injustice around us, we’d do well to allow ourselves be angry, as long as we do not sin, but rather are ignited to compassionate and courageous action.

The gospel does not call us to sullenness, the gospel does not call us to wrath, the gospel does not call us to mildness, but to acts of love and to acts of justice, to acts of great courage and outrageous hope.

Thanks be to God.