I’m going to do something that I rarely do in a sermon, which to share at some length about my own religious journey. I’m going to do this not for the sake of talking about myself, which I don’t really like to do, but because I think it’ll be the most authentic way for me to address some important questions that come up around Easter about what crucifixion and resurrection have to do with salvation. So, I pray that my testimony is helpful to you all in your own journey with God and your faith.

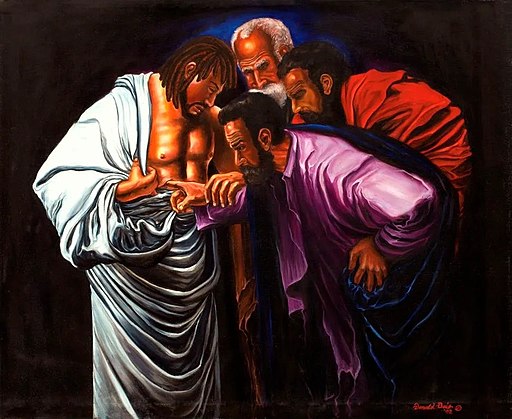

For a long time, I’ve felt kinship with “doubting Thomas.” Here’s the story.

I grew up going to church every Sunday. I come from an extended family where church and faith are really important.

And from a young age, for me, God has been very real. And the spiritual dimension to life was very much alive to me from a young age. What I experienced in prayer and a lot of the words and the stories and music I heard in church gave me a real sense of holy presence, Holy Mystery, this astonishing, beguiling mystery of the Divine.

Also, from a young age I really took seriously the “thou shalts” and the “thou shalt nots”, and especially the teachings of Jesus about how to treat each other. I got that it’s really important how we treat each other and that it has something important to do with God and who God is and who we are. I also started to get that it could be really hard to live like that, and that we lived in a world where people could be cruel and unfair and uncaring.

The other thing to know is that also from a young age I was someone who just thought about stuff a lot, and I was very curious to learn and to read about religion and about everything else in the universe. I loved science; I loved learning about other religions and cultures. And I genuinely wanted to try to figure out how it all fit together.

So, when it came time for confirmation class as an early teen, I was full of questions, questions about what they were teaching us about God and Jesus and the Bible. I was genuinely hungry to figure this stuff out and to test it, to explore God and what we believe about God and why. But that’s not how my confirmation teachers and my pastor saw my questions: they acted like my questions were threats. Not my parents: my parents were great. But I got the message from religious authorities to not be a “doubting Thomas.”

You know, Thomas the disciple who wasn’t lucky enough to be there with the other disciples when the resurrected Christ showed up to them. When they told Thomas about it he said, “Whoa, I won’t believe that until I see it myself.” Don’t be like Thomas, I was told. But I was like Thomas, I couldn’t help it. I thought it was pretty reasonable to not just take people’s word for what I was supposed to believe.

But I was told there is one correct creed, one correct understanding of that creed, and even entertaining the idea that it could be different was dangerous and imperiled my very soul.

One of the big things about what I was told to believe that just genuinely perplexed me was the idea that God had sent his only begotten son (and it had to be “he/him/his” for God, which also puzzled me) to be a sacrifice to himself because only the sacrifice of a morally pure godman would save humanity from God’s wrath at how depraved we are by original sin. Because of the sacrifice of Jesus on the cross God will forgive all of humanity for being born into original sin.

This did not make any sense to me, and no one was able to explain it in a way that spoke to my heart or lined up in my head. It seemed to me to be a bloody transaction that just didn’t fit with my experience and my understanding of a God of love who we are called to emulate in how we treat each other.

What happened to Jesus – crucifixion – was terrible and wrong and shouldn’t happen to anybody, much less to dear Jesus, and I didn’t think that any loving father would want that or demand that for their son, even if there was resurrection in the end. I just didn’t understand how violence should be necessary for forgiveness. It certainly didn’t help me to feel forgiveness or grace for the ways I feel like I’ve fallen short, or feeling forgiveness about the ways other people can be really terrible to each other.

But I was told you had to believe this and exactly this to be a Christian, and if I didn’t then God’s wrath would be upon me.

So, I decided, that, well, that must mean I’m not a Christian. There were other hypocrisies I was mad about, and other theological matters that didn’t add up for me. I did feel sad about it, and something closed-down in my soul. But I was also mad enough and 18-years-old enough, that I totally embraced being a rebel free-thinker who was smarter than millions and millions of deluded people.

Then a couple of very sad things happened in my young adulthood.

I graduated high school in 2001, the terrorist attacks in New York & DC happened when I was just starting college. When I was watching the live news of this, I was standing right next to someone whose brother worked in the World Trade Center.

Several people I went to high school with enlisted in the military, in response, most of them for really virtuous reasons, not all but most. One of the enlistees was this great guy who had been a teammate of mine in track and cross-country, Mark Maida – he was just the most good-natured and upright guy, who was always ready to help. In the Army he became Sgt. Mark Maida, and he was beloved and respected by those he served with.

At the age of twenty-two Mark was killed outside of Baghdad by a roadside bomb.

And he was killed on my birthday, which just brought it home all the more painfully for me.

I had been following the wars very closely. I was worried about the people I knew there, distressed about all the Iraqi civilians getting caught in the cross-fire, I did not honestly think the whole bloody adventure was a good idea – I was just feeling the tragedy and chaos of it. But Mark’s death really broke me open to a much bigger heartbreak. There’s a line in a Carl Sandburg poem about those who were killed in World War One, the endless miles of trenches of dead, where Sandburg writes about being “fixed in the drag of the world’s heartbreak.”

“Fixed in the drag of the world’s heartbreak” – That’s how I felt then and often have felt since. One grief leads to another and another and dozens and hundreds and thousands and millions of griefs over those who die by violence. Fixed in the drag of the vicious cycles of violence. And it just seemed to me to be so tragic and senseless, ultimately, the blood of millions of Abels and millions of Cains crying up to God because we can’t seem to stop violating the 6th Commandment. Does it really have to be like this? How much sacrifice does it take?

And then, with all of that on my heart, the fact that Mark was killed on my birthday just hit me with, “Well, what am I doing with my life? How am I stepping up? What am I doing about how messed up things are? What am I doing to try to respond nobly to these crises of times?” The answer at that point was, not much.

Then I also lost a dear friend, Alice Swanson, also at the age of 22. She was riding her bike to work at a nonprofit in DC and a truck hit her. Alice was the most extraordinary soul – this random and senseless thing could not have happened to someone whose life was filled with as much spirit and love as Alice’s. “Blessed are the pure in heart. Blessed are the peacemakers” – that’s Alice. She knew, clear as a bell that the world should be a better place and the world could be a better place. She had this courageous love which compelled her to work with people dealing with war and poverty in Central America and the Middle East – she spoke Arabic and Spanish, real smart. For the world to lose her at the age of 22… just devastating.

Alice was a Catholic, a Catholic Worker kind of Catholic. I had tried arguing with her about religion, remember I was angry about religion at this point, but she’d always disarm me with her sweetness and her clarity – God was simply real to her, vividly real, and that meant love will win in the face of the worst the world can bring. This start to wake something up in me.

Alice and another friend had talked me into going with them a couple of times to a community of Catholic and Quaker and Mennonite peace people, called The Agape Community, Agape being the Christian word for divine love. This was a community of Christians who all were dedicated, life and death, to laboring to make the world a more peaceful place. They all had this astonishing clarity that this was possible, we can help make a world free of violence, because God is real and Jesus is God’s Anointed. The people at Agape were not naïve in this, many had known violence very early in life, there were several combat veterans. And they did good hard work in the face of real suffering.

After Alice died I decided I had to go to Agape again. I went on a retreat they put on. And at this retreat someone shared about Thomas the disciple – remember Thomas was my guy, doubting Thomas. According to the story in the gospel of John, after Thomas heard the other disciples report about the risen Christ, and he said, “Well I’ll believe that when I see it for myself,” the risen Christ obliged. Jesus showed up to Thomas and invited Thomas to place his hand into the wound in his side. The person telling this story in the retreat evoked the tenderness of this moment when Thomas touched what she called the “world-wound:” the wounds of all the world, born by the body of God. These wounds are due to the ways that we humans can be so wicked to each other, and defy the holy ways of our God who created us to be good and do good. Through the human manifestation in Christ the Creator God shows us that God knows all these wounds, bears all these wounds, and, in the resurrected body embraces us and bear us all through into a renewed life, free and whole.

Hearing this moved me so deeply. I knew something of this world-wound. It reawakened my sense of connection with God. I didn’t feel alone in being fixed in the drag of the world’s heartbreak; I didn’t feel insane for feeling it. And this vision of divine companionship helped me to not be stuck there but to allow God to use our sense of the senselessness of sin to call us back to our senses.

From this point, I began to learn about a much more ancient way of understanding the meaning of the cross and resurrection and salvation. Some people call this Christus Victor – the victory of Christ.

I learned that in Christian history there have been different faithful ways of understanding atonement.

What we usually learn in the modern Christian west is called “penal substitutionary atonement theory”: in order for God to forgive original sin he required a sacrifice that humanity couldn’t make, so he sent Jesus to take onto himself the punishment of God’s wrathful judgment. If you believe this then God will forgive you and you get to go to heaven; if you don’t believe this, then Christ’s blood won’t protect you from the avenging angel of God’s wrath for the original sin that infects you. Penal Substitutionary Atonement wasn’t developed as a doctrine in the western world until the 16th century. The open secret is that this is not the belief in the Eastern Orthodox world – it is by no means to only way to be Christian.

There has been a long-standing ancient faithful understanding called Christus Victor.

In this view, the violence of the cross was not God’s doing or God’s will, just the opposite. Rather, the Resurrection shows the ultimate victory of divine love over the powers of evil, which deny that love.

The ancient Christian image for this is that evil is a kind of sea monster in the murk of falsehood. Christ on the cross is like a fishing lure, to lure out the forces of evil from the deeps – but it’s a trick – the cross is a hook that traps the monster when it attacks and hauls it up into the air and light of divine truth, where it dies. And those souls who were held enthralled by evil are then freed.

Through Christ there was the embodied union of the human and the divine. In response, all the powers of evil lashed out – all the powers that deny divinity and deny humanity, what we call sin: hate, greed, lust, envy, exploitation, domination, all of it, were dead set on destroying Jesus. The powers-that-be, fallen from their original good God-given purpose, scapegoated Jesus as a criminal, a traitor, a foreigner, a heretic. Like countless others before and after, the unholy union of mob violence with state violence, abetted by mob mentality executed Jesus. This is the opposite of what our Creator wills for creation, and yet we know it happens.

Through Christ’s death, God shows that God godself bears the pain of all this, which so many throughout history and to this day suffer. God bears the pain and tragedy of the world-wound. God loves us through it, all of us, whether we’re the ones suffering or perpetrating.

Then, through Christ’s resurrection, God shows evil and sin to be ultimately powerless, self-defeating illusions, that just melt before the ultimate power and love of God.

God loves and forgives humanity whether we like it or not, whether we fight against it or surrender to its sweetness. When we see the truth of this, the truth sets us free. We are saved from the senselessness of sin; we are restored to our senses as children of the living God.

This is indeed Good News. I am so grateful for it.

This is why I can sing with the old hymn:

I know that my Redeemer lives. Glory, hallelujah!

What comfort this sweet sentence gives. Glory, hallelujah!

He lives to crush the pow’rs of hell

He lives, within my heart to dwell

He lives, my hungry soul to feed

He lives to help in time of need

He lives, triumphant from the grave;

He lives, eternally to save!

He lives to heal and make me whole;

He lives to guard my troubled soul.

Glory, Hallelujah!

Delivered Sunday, April 23, 2023, at the United Church of Christ at Valley Forge, by Rev. Nathaniel Mahlberg

Image: Doubting Thomas oil on canvas painted by Donald Dais- Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

This is beautiful. I relate with your story on many levels! And I had never heard “Christus Victor” explained so well before. Thank you for sharing, Nathaniel.

LikeLike