I invite you to think about a time when you did the right thing despite social pressure to do otherwise. When was a time when you listened to your conscience over and above other voices telling you to ignore it? When have you followed your moral compass when that meant going against the flow?

Maybe it was something little, or something big, something subtle, or something dramatic. Every act of moral courage is important.

Then reflect, if you would, on what helped you to do that. What led you to act or to speak up? What prepared you for that? From where did you draw strength? From where did you find support?

Then, I invite you to think about a time when you didn’t, when you let social pressures over-ride your sense of what is the right thing to do. God is merciful, we can be honest with ourselves, before God.

It’s very important to reflect on the times when we did not have the moral courage we wish we could have. What social forces, what forces within ourselves led us to muffle our moral misgivings, to stifle our conscience. What fears, what threats?

Perhaps there’s even a situation in your life right now where you’re wrestling with what is the right thing to do, or wrestling with knowing what the right thing is but fearing the consequences of acting on it.

An important part of a life of faith is being challenged to grow in our clarity of conscience and in our courage of conscience, even as we grow in our honesty about our moral blind-spots and moral weaknesses, and honest about what is just difficult and fraught, about the moral ambiguities and ambivalence we face as fallen creatures in a fallen world.

What does it take to do the right thing, when doing the right thing is hard?

There’s a famous psychological experiment from the 1960s. An advertisement went out offering to pay people to participate in an experiment about how we learn..

When people came in to their scheduled time to participate, they met another participant and Dr. So-&-So of Yale University in a white lab coat who explained that this is an experiment about memorization and the role of punishment in it. He explained that one participant will be the teacher and the other the learner. The two participants drew straws about who would be the teacher and who the learner. What the person who became the teacher didn’t know was that the learner was in on the experiment and the drawing straws was rigged.

The person who became the teacher was actually the subject of the experiment.

The psychologist took them in to a room, the learner was seated behind a screen. The teacher was seated at a desk with a button to push and some memorization lessons. The instructions were that if the learner failed to get the memorization right the teacher would push the button which would give the learner a shock. Each time the learner got an answer wrong the voltage of the shock would increase. The teacher could see a meter with the voltage. The meter marked the higher voltages with orange and then red, which said dangerous and fatal.

Now remember the learner was in on the experiment, he was an actor. And he was behind the screen so the teacher couldn’t see him, but he could hear him. They could hear the learner’s answers and hear how they responded to the electric shock.

The learner, who was a plant, was not good and got a lot of answers wrong. So, whoever was the teacher then had to push the button and shock the learner and then heard them yelp. And the voltage meter increased.

This whole time the psychologist, the doctor, was there in a lab coat telling the teacher to administer the punishment.

You can see video of this. It’s famous: Stanley Milgram’s obedience experiment. From the 1960s. Just search online if you want – it’s excruciating to watch, so don’t look it up if you don’t want.

What you will see is that most participants get really anguished about this, they don’t want to go through with what they believe to be hurting somebody. As they voltage increases with each wrong answer the actor playing the learner starts to beg and plead for this to stop. The doctor stays firm and stern in his commands.

But even though the participants become really anguished about it all, a huge percentage of them were willing to obey the orders to keep pushing the button and doing what they believed to be dangerous or even lethal harm to another human being.

It’s very sobering … but maybe not surprising if we look at history and at our own lived experience and see that it can be all too easy for regular ordinary decent people to get pushed by authorities into harming the most vulnerable among us or how easy it is to just pass by and ignore the cries of those who are harmed in our name.

Now, when we hear about an experiment like this, those of us who like to think of ourselves as good people may all imagine ourselves being the ones who stand up and refuse and say, “No! This is cruel. This is insane. I’m out of here.” The chances are, though, that the majority of us would have let ourselves get railroaded into it.

I should say that Stanley Milgram was criticized for leaving out the numbers of participants who refused to participate at the earliest stages, when they learned that it was an experiment that involved punishment. There were more people who refused, over all. But the outcome is still sobering.

Milgram had an agenda (which I would call compatible with Christianity) to break through a self-righteous, self-satisfied American self-conception about how morally superior we are and show people that, no, sorry, in fact we are all quite susceptible to evil. You too.

In the words of Alexander Solzhenitsyn, the Russian Orthodox thinker who wrote about his time in a Soviet gulag, “If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”

What Stanley Milgram and those who followed in his footsteps did was study the social psychology of normal people getting pushed onto the evil side of that divide in our hearts.

Only more recently has there been psychological research into those people who do in fact do the right thing despite social pressures. This is very important. What can we learn from the people in Milgram’s experiment who let their conscience speak and refused to do more harm, or those who refused to even participate once they learned that the experiment involved administering punishment – “No, I don’t care that you’re paying me, I’m not doing that!”?

This is also I would say a quite Christian concern. Being honest about our moral weaknesses is no excuse for cynicism or despair – we each do in fact also have the capacity for moral courage.

What this research has found is that those who demonstrate moral courage in various experiments are quite diverse in their backgrounds and beliefs. But one thing most of these folks have in common is they each in their own way report they belong to a community or a family that has clear moral beliefs and that has prepared them for that morality to be tested. These folks have been prepared to not be naïve about the fact that there are forces in this world and in ourselves that can make it easy to not do the right thing and hard to do the right thing. And they have a sense of greater belonging that gives them strength to do the right thing even if in the moment they are in alone in doing so

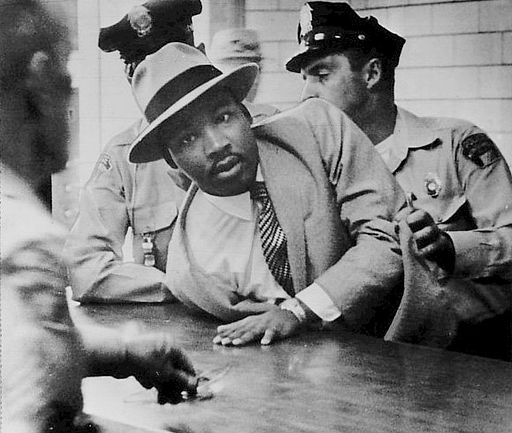

When Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. faced his first life-or-death test, his church and the faith of his family had prepared him for that moment.

This was just a couple of months after the start of the boycott of the racist segregated bus system in Montgomery, AL, early 1956, just a couple of months after this young preacher, in his mid-twenties, with his young family, new to town, had been thrust into a leadership role in this local resistance movement. He had been reluctant to take that on, but the leadership in the Black community (many of whom were women, by the way, and unsung in their intelligent, disciplined preparation of a movement to jam the system of racism) these leaders had wanted a fresh face to be a spokesperson for the movement, so they talked this young promising new preacher into it.

Dr. King was reluctant, but he said “Yes.”

Very quickly the movement took off. And very quickly the forces of racism bit down as viciously as it could. Dr. King was soon arrested for the first time, for driving 5 miles above the speed limit, and spent a very unpleasant night in jail. When he was released he came home to phone calls of chilling threats against him and his family.

As he would later relate, this caused in him a crisis of confidence.

Alone at night after his wife and kids were asleep in bed, he was at the kitchen table, worrying and doubting and perhaps wishing he could somehow get out of this.

He realized what he needed to do was to pray.

This was his prayer:

“Lord, I’m down here trying to do what’s right. I think I’m right. I think the cause that we represent is right. But Lord, I must confess that I’m weak now. I’m faltering. I’m losing my courage. And I can’t let the people see me like this because if they see me weak and losing my courage, they will begin to get weak.”

This is what happened next, in his own words: “I could hear an inner voice saying to me, ‘Martin Luther, stand up for righteousness. Stand up for justice. Stand up for truth. And lo I will be with you, even until the end of the world.’ … I heard the voice of Jesus saying still to fight on. He promised never to leave me, never to leave me alone. No never alone. No never alone. He promised never to leave me, never to leave me alone.” (From “Bearing the Cross” by David J. Garrow)

This prayer is a glimpse of very human vulnerability in someone we rightly look to as a model of moral courage. This prayer I believe can be a good model to us to help us each in whatever station or circumstance of life we are in, to be prepared to do the right thing despite our weaknesses or fears, despite our feeling alone in the moment, in whatever situation, big and dramatic or small and humble. Every act of moral courage is important.

“Lord, I’m down here trying to do what’s right,” King began, “I think I’m right. I think the cause that we represent is right.”

1. The prayer starts with expressing the desire to be connected with God and to live according to what is right. Very important to not forget then.

“But Lord,” he continues, “I must confess that I’m weak now. I’m faltering. I’m losing my courage.”

2. The prayer next moves to a confession of how he feels about the challenge. It is so helpful to be honest to God about our weaknesses, in ways we perhaps don’t even share with anyone else.

Then Dr. King prays, “I can’t let the people see me like this because if they see me weak and losing my courage, they will begin to get weak.”

3. This step is crucial. He connects with his community, with the people he cares about and belongs to and is accountable to.

And then at last he waits, open to however God will respond.

How does God respond? By embracing him with a larger belonging. He is not alone, but the Lord is with him. When we do the morally courageous thing and we can take courage that God is with us.

As Dr. King would later say, “The time is always right to do what is right.”

What does that mean for you now? Is your conscience unsettled somehow with something in your life? At work? In your relationships? In your way of life? In daily decisions? In our society? In our world? Especially considering the enormity of what Dr. King called the “triple evils of racism, poverty, and war,” discerning what is right and doing what is right can feel daunting.

Whatever our station in life, whatever our opportunities and challenges of doing the right thing, despite the forces that act on our moral weaknesses, despite the pressures to just be quiet and safe and go along with whatever is distressing our conscience, Dr. King has given us a model for prayer that can help us all to do the right thing, and know that God is with us, and that we’re all in this together, that we are never alone, no never alone.

Thanks be to God.

Delivered Sunday, January 14, 2024, by Rev. Nathaniel Mahlberg, at the United Church of Christ at Valley Forge

Image: Martin Luther King, Jr. Montgomery Arrest, 1958, Associated Press, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons