Let me begin with a poem:

“St Kevin and the Blackbird”

By Seamus Heaney

And then there was St Kevin and the blackbird.

The saint is kneeling, arms stretched out, inside

His cell, but the cell is narrow, so

One turned-up palm is out the window, stiff

As a crossbeam, when a blackbird lands

And lays in it and settles down to nest.

Kevin feels the warm eggs, the small breast, the tucked

Neat head and claws and, finding himself linked

Into the network of eternal life,

Is moved to pity: now he must hold his hand

Like a branch out in the sun and rain for weeks

Until the young are hatched and fledged and flown.

*

And since the whole thing’s imagined anyhow,

Imagine being Kevin. Which is he?

Self-forgetful or in agony all the time

From the neck on out down through his hurting forearms?

Are his fingers sleeping? Does he still feel his knees?

Or has the shut-eyed blank of underearth

Crept up through him? Is there distance in his head?

Alone and mirrored clear in love’s deep river,

‘To labour and not to seek reward,’ he prays,

A prayer his body makes entirely

For he has forgotten self, forgotten bird

And on the riverbank forgotten the river’s name.

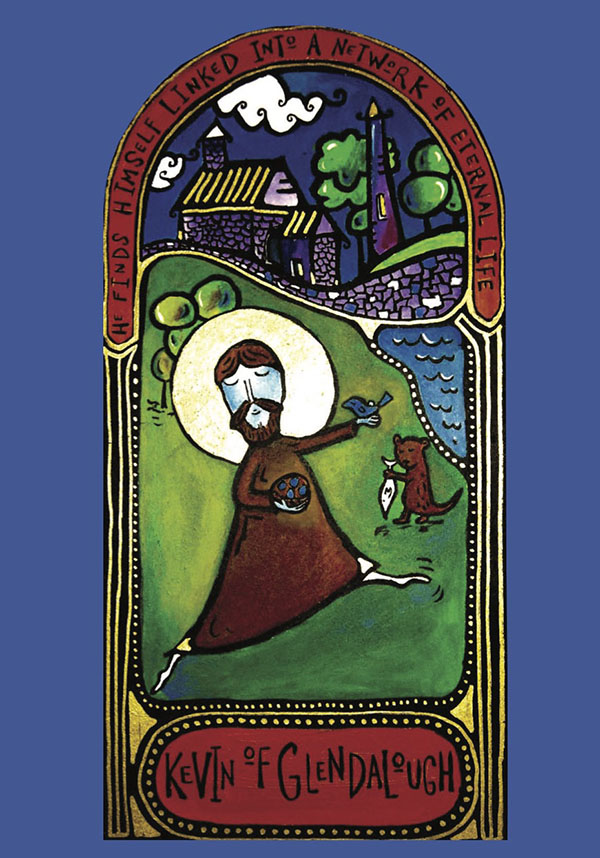

St. Kevin and the Blackbird is such a moving image of a Christ-hearted care for the creatures of God’s creation.

St. Kevin becomes like a tree, for a season, for the sake of a mother bird and her young.

This can be a kind of icon for the humility and the responsibility one can feel for Creation when one has devoted their entire being to living a life centered on God.

Now, when Seamus Heaney wrote a poem about this old story of St. Kevin and the blackbird, he doesn’t let us just admire him.

He asks us a very real question: Can we imagine ourselves in his position? And if we imagine ourselves in his position how would we feel? Would we be in agony or ecstasy?

Seamus Heaney helps us imagine both.

He helps us imagine our bodies in agony stuck with our arms out in this contorted posture, day after day, week after week. Most of us probably imagine we would feel that way.

But most of what this poem does is invoke a kind of quiet ecstasy, a sweet self-forgetfulness, that comes in these times when our compassion grounds us in something much larger than ourselves, which supports us to grow through our discomfort, in our care for another creature:

“finding [oneself] linked

Into the network of eternal life” …

“mirrored clear in love’s deep river” …

“A prayer [one’s] body makes entirely

For [one] has forgotten self, forgotten bird

And on the riverbank forgotten the river’s name.”

This poem invokes the kind of spiritual experience that can come when we surrender ourselves in our care for another, make a prayer of one’s entire body, entire being, and in so doing surrender ourselves to the great Being of our Creator.

The reality for most of us – for all of us, probably, even saints, is that there can be both agony and ecstasy in this level of sincere caretaking for another, this dedication to one’s responsibility to not let another life down.

Have you cared like this for another life? Another life of your own kin? Of another’s kin? Of another kind of life altogether? A life with wings or fins or fur or leaves?

It doesn’t take a saint. But it does stir within us something of the kind of spirit that is very strong in saints.

There are lots of these kinds of stories about saints. It’s a long and abiding theme in the stories and images that folks have told about those called saints, about the people through history who best show us how to follow Jesus and have the heart of Christ in living centered on the reality of God: One of the special things about them is their radical compassion for all beings. Saints tend to have a peaceful and loving influence on not only other humans, but also on all kinds of animals, that helps bring about their health and fertility and flourishing. St. Francis is the most famous example here.

This image of St Kevin and the blackbird can serve as a kind of icon for the longstanding traditions within Christianity of care for creation.

This is a longstanding Christian tradition: that understand that one of the ordained purposes of human beings is to be humble stewards of the gift of this good earth, to take responsibility for the well-being of this world. In return we are blessed by the rich sustenance that the earth and its creatures can provide.

The Hebrew scriptures are full of love songs of a people for their land, for the beauty and abundance of creation, for the awesome God who creates it all and entrusts it to us as a precious gift. Scriptures are full as well of songs of awe: before the raw power and scope of the forces of land, and water, and fire, and wind, the forces of fertility, of life and death, all but glimpses of the unbounded power and wisdom of God, the Holy Creator.

Scripture sings of humility and of responsibility before this sacred reality.

The Hebrew scriptures see the land as an inheritance – we receive it as something we didn’t earn, and it’s our job to caretake the land and share its fruits in a just way so we can maintain its fertility for the next generation and beyond.

So, how are we doing with that purpose, as humankind right now?

How are we doing with that humility and responsibility?

Let’s be honest: Are we taking good care of the fertility and abundance of this good earth, so we can pass this inheritance on to those who come after us?

The truth may be painful: There is good reason to expect we will be giving to our children and grandchildren a much more depleted and severe earth than the earth we received. Not to mention the children and grandchildren of other species.

One of the many ways our culture justifies its appetite to just take and take and take is a perverse form of Christianity that says that, well, God gave us this world for us to conquer. Full-scale domination is our God-given birthright as a species.

Or some have that view that, let’s be real, taking yours to get mine is just the law of the jungle. Maybe we can applaud the saints and their compassionate care, but in truth they’re deluded. And it’s deluded to think that we all should live that way. We’re all sinners who fall short of unrealistically high ethical standards. That’s why we need Jesus as the perfect man to serve as our savior.

And who cares about this world anyway? All that really matters is the world to come and making sure we believe the right things to get to heaven. It doesn’t really matter if we trash this earth behind us. God’s going to burn it all down in the end anyway.

For what it’s worth, I think this view of Christianity doesn’t do justice to Jesus and the Hebrew Prophets. It is much more a belief system of the Roman Empire and the empires that came after which then used the Bible and Christianity for its own purposes. But I won’t get into that now.

For now, I want to lift up St Kevin and the Blackbird, and the traditions of creation care within Christianity that says that part of holiness is striving to live well with the earth and its creatures. The nearer we are to the heart of Christ the humbler and more responsible we are toward all Creation.

Alright, sounds nice, right?

But as we consider this story of St Kevin and the Blackbird as a kind of icon for the Christian value of care for creation, let me question something about:

What do we make of this ideal being someone who totally selfless and self-denying?

“To labour and not to seek reward.”

Is it realistic or even helpful to have this kind of selfless and self-denying ideal? The martyr/saint?

Does it have to take a saint to be a good steward?

Because there are problems with that, especially when it comes to talking about environmental issues.

We do need to harm some things to survive. That’s a fact.

Food, clothes, and shelter – it’s all from plants, animals, and minerals. Those have to come from somewhere, in ways that often require taking life. We can’t pretend we can somehow become pure enough to not be destroying some things in order to create what we need to live.

But if you are someone inclined to really be concerned about the melting ice caps and rising sea levels and increasingly severe floods and fires and heat waves and famines, and the mass extinctions, and all the tremendous suffering of all that, which in recently years has become impossible to deny … and if you’re inclined to take seriously that humans bear responsibility here, that the massive scale of human industrial production and consumption has been changing the atmosphere and oceans and driving the changing climate in measurable and prove-able ways … it can be easy to just feel overwhelmed and helpless.

There can be this feeling that there’s nothing we can do, or that the only things we could do require us to become a saint or a martyr. You have you have to be going completely off grid and only eating the fruits and nuts of your trees, or you have to be putting your life on the line to block pipelines, or you have to be rushing off to aid every flood and famine, or you’re just a hypocrite.

This can be paralyzing.

What the martyr/saint image misses is that care for creation really is mutually beneficial. The true nature of our relationship with the more-than-human world is reciprocal, it’s relational.

St Kevin and the Blackbird does a beautiful job of showing the kind of humility and responsibility that we are called to, but focusing too much on just Kevin misses the bigger picture.

How did Kevin eat?

He ate because other people who cared about him came by and gave him food. That’s how monastics were supported. It was the community around him that made St. Kevin’s sanctity possible.

Kevin was himself in a nest that was held by a generous community.

And this human community itself was supported by a dense weave of ecological relationships that contributed to the flourishing of their agriculture and trade.

It impossible to list all the different living beings who contribute to a thriving pre-industrial agricultural village. Just a square inch of rich soil has such an impossibly complex ecology of organisms that some scientists have said we know more about outer space than about what all goes on down there.

So, you see:

The mother bird and her hatchlings were themselves part of a vast weave of relationships that supported Kevin himself, like a nest as big as the landscape. Birds are very important to thriving ecosystems, after all. As Seamus Heaney put it, Kevin, with that mother bird in his hand, found himself “linked into the network of eternal life.” He simply did his part to support part of what all supported him.

Many indigenous wisdom traditions teach an ethic of sacred balance in human relations with the more-than-human world. This ethic recognizes the ecological fact of the complex web of relations that give rise to flourishing life. We live well when we live in alignment with this sacred ethic, which comes from the Holy Creator.

When one must take life for the survival of one’s family, one must give something in return to restore a balance between destruction and creation: “Spiritual reciprocation,” in the words of some contemporary Native American religious thinkers (Kidwell, Noley, & Tinker, “A Native American Theology,” pg. 41)

But when we forget that sacred responsibility and any one species dominates at the expense of the larger ecosystem, they are setting things up for a collapse. Booms & busts don’t just happen in human economies, they are a problem in ecosystems that are out of balance.

When we don’t do our part, we hurt ourselves. When we are severed from the reciprocity of relations with the wider world, we suffer, along with others. We have to admit that in our civilization so alienated from our natures as part of nature, we are suffering and causing suffering in this way.

The positive side to this is that any way we have to reconnect and reawaken to our wider belonging is a life-giving, soul-renewing experience.

It doesn’t need to take a saint.

Many people who are the most focused on what’s needed to change course have concluded that a spiritual shift is just as needed as material shifts.

The good news is that this kind of spiritual shift is good for us on a deep level.

Everything we do to address the crisis of environmental devastation can be life-giving, community-growing, full of hope and good news. Working together in the dirt and planting seeds and sharing the fruits just feels good. Because it is good.

It’s our job as Christians to offer hope and to bring people together around that hope. This is about Good News and New Life, after all.

The wisdom and testimony of the Hebrew and Christian traditions should lead us to know that when we come together as a community to care for our inheritance of this good earth in a way that is just and fair, God will bless us with continued enjoyment of the earth’s fertility and abundance.

The world is not ours to save. We need to allow ourselves to be saved along with the rest of the world. While that may require simplified lives, it’s a gift to be simple, a gift to be free.

Knowing God to be at the heart of things, Kevin was full of joy.

The needs are urgent.

But this is a responsibility we can meet with great joy and hope.

Thanks be to God.

You can view video of this sermon here.

Delivered Sunday, September 15, 2024, by Rev. Nathaniel Mahlberg at the United Church of Christ at Valley Forge